Baba Link Farm: Exploring the Heart and Art of Agriculture

“When I first met my husband, he said ‘You’ll never leave the farm!’†laughs Pat Kozowyk. At the time, Pat was an established artist in her late twenties, with no interest in taking over the family business. Now, years later, as owner and operator of Baba Link Farm, she has had to admit he was right.

Farming is not for everyone. It involves long hours and hard labour. Crack-of-dawn harvesting and dirty knees. Low pay and little thanks. When urban dwellers romanticize food production, farmers laugh to themselves, knowing the weather-beaten reality. Yet there is a connection to the land that goes deep, and this is what draws people into the profession.

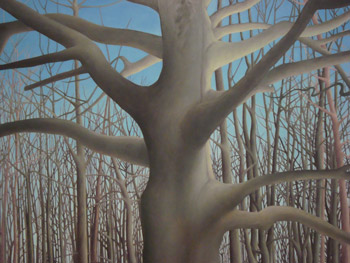

When Pat walks her orchards, she stops by each tree and tells a story. Despite the dazzling number of heirloom fruit and berry varieties, she can remember all the names, and the nurseries where she purchased the stock. Indistinguishable green shrubs transform into rich depositories of history and lore.

This interest in varieties stems from Pat’s artistic inclinations: “Growing up, I painted the trees on the farm, and became interested in the story behind each tree. So I did my research. When we took over the farm, this extended to the fruit I grow.â€

Pat refers to her gardens as her “large art installation.†A farmer-adventurer, she searches out exotic varieties and old-stock. Apples named Melrose, Meigold, Irish Peach; pears named Bonne Louise, Winter Nellis, and Aurora. “This is an Asian Pear variety named Shinseiki,†she explains, pointing to the hard green balls. “The fruit will ripen in a month or so.†Through her words, you can almost taste the fresh juice and satisfying crunch.

The Baba Link orchards look different from other orchards you see along the highway. Instead of long straight lines, the shrubs, vines, and trees arc with the shape of the land. Instead of careful cloisters of grocery-store varieties, you get an abundance of tastes, textures, and colours. Pat got her inspiration from a gardening book published at the turn of the century. “It’s called the ‘messy orchard,’†she explains with a grin.

Yet there is method to the messiness. Pat knows the land inside and out, and there is careful research behind the aesthetics. One of the biggest critiques of industrial agriculture is how it manipulates nature to mass-produce food. Instead, Pat farms organically, and goes by a philosophy of light touch and listening. “It helps having grown up here, knowing the different types of soil, humid spots and moist areas. The orchard likes a nice breeze going through, and I know where there’s a good wind flow, so I plant accordingly.â€

She nurtures her plants, and has a deep-rooted knowledge of what makes them grow. Stopping by an abundant crop of Jerusalem artichokes, she notes, “This stand thrives because it is planted on top of an old tree, and the tree mulch gives it life.†All around the farm, each plant is honoured: the black walnut tree in the orchard makes delicious syrup as well as calligrapher’s ink. The springtime nettles make fine soup for local restaurants.

Pat learned much of this organic philosophy from her mother. Alex and Betty Kozowyk bought the farm in 1954, and moved their whole family from Toronto to Flamborough. Pat’s father Alex continued his work as a pipefitter, while Betty began full-time farming.

At that time, Flamborough was mostly farm fields and bush lots. The farm itself speaks to a long history, and pays testimony to rural development, commerce, and conservation. On one side, the farm is bounded by Canadian Pacific railway tracks. On another, an Enbridge pipeline. The lower orchards are nestled close to the Flamborough Centre wetlands. Since 2005, the farm has also been part of the Ontario Greenbelt: 1.8 million acres of protected, legislated land that safeguards farms from urban sprawl.

Pat’s mother deeply respected this landscape. When introduced to chemical sprays in the 1960’s, she tried them once, and refused to use them again. Instead, she farmed with nature in mind, fostering a diverse mix of livestock, hay, vegetables and fruit. Her special passion was the raspberry patch, where Pat spent many childhood hours working alongside her mother.

When Betty Kozowyk passed away in 1984, Pat and her husband Ernie returned to the farm to help Pat’s father, and maintain the beloved raspberry plot. After two years, the couple relocated to the small town of Freelton –but a seed of possibility had been planted.

Several years passed before they began to seriously consider buying the farm. After much discussion, they sold most of the land, and retained a ten acre portion. It was named Baba Link Farm, in memory of Pat's mother, "Baba" Betty. Baba is Ukrainian for Grandmother. The logo for the farm is based on a Ukrainian folk art design, and resembles the Bobolink birds that sang all summer in the pasture. In 2002, Pat, Ernie and their young son Philip returned to the countryside.

When looking back, Pat acknowledges the deeper reasons that spurred her return: “It wasn’t simply the growing and harvesting that hooked me. It’s seeing the deer every time you walk to the woods. The squishiness of clay mud on bare feet. It’s about knowing the sound the tall pines make in the wind.â€

She hopes she has raised her son with similar sensibilities: “I don’t know if he will want to continue with the farm, but my parents never expected me to do what I’m doing. It is enough to let the land seep into one’s being—and then just see what form that experience takes.â€

She speaks fondly of Philip’s involvement in the business. When they first returned to the countryside he was in grade three, and helped plan the first apple and pear orchards. Now, at sixteen, Philip helps at market, understands the realities of the farm operation, and on occasion convinces his buddies to help pick the berries.

Philip also led Pat to discover the “best berry she’d ever tasted.†It all started with Philip and a neighbourhood friend. The friend would be driven to the farm by his mother, and Pat would always offer her raspberries to eat. Each time, the woman would try the berries and politely say, “These are great, but my mother grows the best berries.â€

Curiosity eventually called for a visit to this neighbouring farm. In the garden grew a variation of the heirloom “Cuthbert†raspberry. Even better, this was a Cuthbert Improved, acquired from the Rayners’ farm, four concessions over.

After bartering tomato plants for raspberry canes, Pat tried the famous berry. “It was like a fine wine. First a tart sweetness, then a velvety spice, then effervescence. Having a berry do three things in your mouth is absolutely lovely.â€

Pat told this story as she offered me one of the Cuthbert’s Improved-- sun-warmed and a deep maroon colour. I took it gingerly. After that lead-up, would I be disappointed? I put the berry into my mouth. It was bliss. A fine wine. Pat watched appreciatively.

As we went back into the farmhouse, I let my gaze linger behind: the landscape layered with stories, some beautiful secrets revealed. Now, when driving through Hamilton, I’ll be able to think of that little farm, tucked off a concession road, growing the best berries I’ve ever tasted.

If you would like to try these berries for yourself, you can find Philip and Pat at the Harbourside Organic Farmer’s Market in Oakville and at Sorauren Park Farmers’ Market in Toronto. You can also visit the farm website: www.babalinkfarm.ca

Baba Link Farm is a proud member of the Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario. For more information, please visit www.efao.ca

For more information about the Greenbelt, please visit www.greenbelt.ca

Photo credits: Melissa Benner and Pat Kozowyk.