Portrait of a Gardener: An Ideal Shade of Green

I recreate and propagate the colour green - the opaque pale jade of a dry pincushion moss, and its ripe lime green that bubbles up only moments after a misty rain; or the deep forest green of a hair-cap, its delicate but lengthy wings outstretched like the corona of the north star.

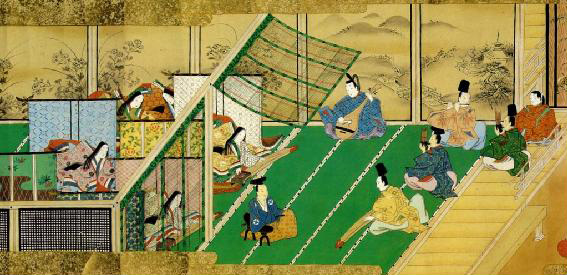

I harbor an ideal shade of green. The recipe lies in the crushed dust of malachite and beryl mixed in the ink of the 17th century Japanese scroll paintings known as Nara Ehon. The green pigment is not within the folds of these figures’ crisp kimonos nor embedded in an elaborate lacquer curio. Instead it is in the simple square tatami carpets unrolled under the paintings’ main subjects. The most exquisite rendering lies in the parchment of the Bunsho no Soushi Emaki. Bunsho, through devotion to a local animistic deity, encounters immense success as a salt merchant and marries his daughters off to royal aristocrats. The scene in the scroll depicts Bunsho’s daughters and their husbands playing music on a sparse veranda. There is only a single sheet of unwavering emerald green kept exactingly sparse through meticulous cleanliness and maintenance, supporting its guests with the firm bows of matured tradition. I do not recreate this hue in a mineral inky pulp, but nurture it slowly from moss. After spraying a mist over my pincushion formations several times a day for many weeks, I think I get close.

Moss is a rootless creature, able to capture moisture only from the paper-thin folds of its tiny leaves. But coupled with this delicacy is unrivaled endurance. When the autumn rains come, the ghost-white, bone-dry cuticles that had lay dormant in the summer heat spring to life. For some it takes two days of consistent watering to restart the engines of photosynthesis. For others, only a ten minute mist is enough to inject life into even the sorriest, most shriveled stalk.

Care for the plant is almost effortless. All that is needed of the gardener is the vigilance and patience to sweep daily for suffocating debris, and wait many long years for its propagation. The Japanese sweep the detritus away from moss with a carefully bound bamboo-branch broom called a takebÅki. Gardeners also wear special skin-tight shoes called jikatabi to tread lightly over the delicate organisms.

It is this long-term time scale that earns moss such a celebrated place in the Japanese landscape. You can try to transplant moss like sod, but the odds are against you. Just ask Japan’s Speaker of the House of Representatives, whose estate garden suffered a massive die-off of transplanted haircap moss.

The truly exceptional examples come only after decades of patience. The Saihoji temple along the Southwest foothills of Kyoto was constructed in the 9th century with a stroll garden paved with wide swathes of sand. Over time it came into disrepair, and eventually passed out of popular knowledge. When it was discovered in the 19th century, a robust and diverse field of moss had taken the place of the sand.

Photo credits: Nick Kraus; Chester Beatty Library (Bunsho no Soushi Emaki)