The Global Roots Oral History Project: Stories from a Multiethnic Garden

We often don’t think of gardens as anything more than sites to grow fruits, vegetables and flowers. But gardens, and the stories that live within them, can serve as unique starting points for understanding cities’ shifting cultural and edible landscapes. The Global Roots Garden is a space in Toronto where the importance of diverse experiences with food and gardening has found room to grow. Housed at The Stop Community Food Centre (The Stop), this demonstration garden is an example of how sharing unique and diverse experiences creates new ways of knowing, learning and interacting with food, plants, land and each other.

The Stop Community Food Centre: Sowing the Seeds of a Story

The Stop, originating in the 1980’s, is a redefined food bank. It is an anti-poverty organization, dedicated not only to the provision of healthful food, but also to nurturing social connections and promoting civic engagement.

The Stop has two locations in neighbourhoods of differing socio-economic and cultural backgrounds. The first location includes a food bank, a drop in service, a community kitchen, a civic engagement program and a community garden. The second location is The Green Barn, which opened in 2009. This space includes a greenhouse, a commercial kitchen, a space for classrooms and the newly developed Global Roots Garden.

The Global Roots Garden Puts Down Its’ Roots

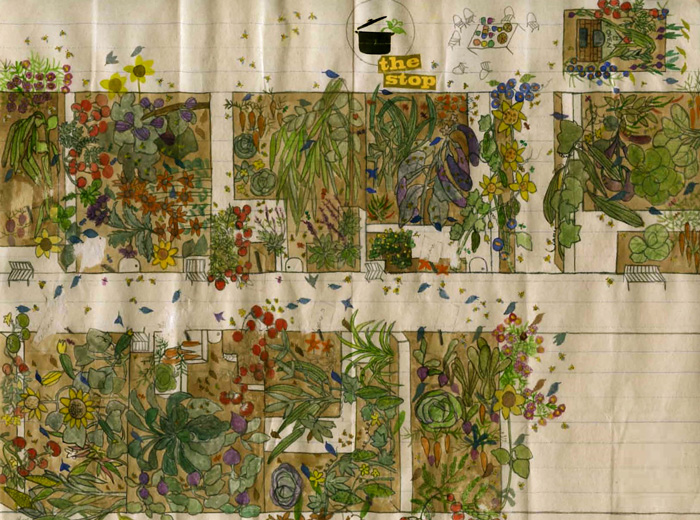

At the beginning of June 2010, I noticed that landscaping had begun beside the Green Barn. Over the next month, the once concrete, under-used space was transformed into beautifully designed garden plots, each separated by small, wooden fences. Crops began to pop up and slowly the space became full of diverse vegetables and herbs, some that I had never seen before.

As a volunteer with The Stop, I grew excited by the transformation of the space. Not only did I notice the many conversations that were initiated between people passing by and admiring the newly planted area, but I also witnessed the ways in which the gardeners from different backgrounds, genders and ages found ways to interact with each other, even with language barriers. Taking breaks from tending to their plots, they often sit, eat and talk (with help from the youth who act as translators) over various dishes.

As a volunteer with The Stop, I grew excited by the transformation of the space. Not only did I notice the many conversations that were initiated between people passing by and admiring the newly planted area, but I also witnessed the ways in which the gardeners from different backgrounds, genders and ages found ways to interact with each other, even with language barriers. Taking breaks from tending to their plots, they often sit, eat and talk (with help from the youth who act as translators) over various dishes.

So what is the Global Roots Garden?

So what is the Global Roots Garden?

The Global Roots Garden (GRG) is a multicultural community garden developed to demonstrate the diversity of crops that can be grown and shared within limited city space. Over 40 people from various cultural backgrounds - Polish, Tibetan, Latin American, South Asian, Chinese, Filipino, Somali and Italian - tend the GRG.

By cultivating diverse crops - okra, bitter melon, Chinese cabbage - the gardeners are sharing new stories of how plants, typically seen as non-local or ‘exotic,’ can be grown in Toronto, changing the narrative of what constitutes local food, and, more broadly, of what it means to be authentic in Canada.

The garden is also a site for newcomers to continue traditions from their homelands, representing a conscious recognition that food can invoke memory and can connect experiences across diasporic communities. I began to think of different ways the diverse knowledge already living within the garden could be unearthed.

The Global Roots Oral History Project: Harvesting the Stories

The Global Roots Oral History Project: Harvesting the Stories

Created in collaboration with members of the GRG, The Global Roots Oral History Project (GRP) is a collection of the gardeners’ stories. The narratives are as diverse as the plants grown within the plots. Some stories reflect their personal relationships with plants and gardening; others are old folktales recollected from the gardeners' countries of origins. The project will be displayed in an audio installation located within the garden and is already active online. These short, personal stories illustrate how everyday experiences with food and a love for gardening can bring people together, crossing cultural and ethnic boundaries.

Garden Stories: Collecting and Sharing the Harvest

Garden Stories: Collecting and Sharing the Harvest

I began the project in September, 2010 by helping the gardeners tend to the garden and harvest the vegetables. While working with the gardeners, I talked with them about plants and dishes from their homelands. The gardeners’ stories often extended beyond the garden, and into their homes. One of the Italian gardeners invited me to her home where she showed me her basement stocked full of preserved vegetables; cans of homemade tomato sauce, drying herbs, fresh bread, meat that was being cured and a freezer full of cannelloni. Her basement is its own story of canning and preserving - of how we can take care of ourselves in sustainable ways and seek alternatives to the current food system.

To draw out stories like this, I facilitated a large story circle at The Stop. I provided questions in order to excavate personal stories that could reflect larger social and cultural contexts. Through translators, this was the first time the gardeners could really listen to each others’ words. The gardeners shared recipes and expressed their excitement in learning how to cook with the vegetables from the different plots.

Others shared stories from their childhood, including one of the Chinese youth who spoke about her mother’s cooking. Christina explained the importance of gardening during the war in the Philippines: “Everybody had to plant, because we had to have food during the Japanese Occupation. My father was a fisherman, so he would go to the river and fish. We would have fish for lunch and also vegetables from our garden.â€

From Story Circles to Interviews: Telling the Garden Stories

From Story Circles to Interviews: Telling the Garden Stories

After facilitating the large story circle, I interviewed the gardeners in smaller group settings and helped them focus on a specific story important to them. Mary Zhu, a member of the Chinese plot, told a story about her favourite vegetable in the garden, Chinese cabbage, a staple ingredient where she grew up in Northeastern China. Shu Rong, also a member of the Chinese garden, shared her vast experiences with gardening and food - from spending her middle school days in rural Sichuan helping farmers during a drought, to trying dumplings for the first time when moving to China’s Northeast (Sichuanese food contains rice as a staple grain while the North is known for wheat based dishes such as dumplings and noodles). She explained living next to an urban farm in Beijing during the great famine and talked about the joy that gardening has brought her since moving to Toronto.

These are only two examples of the stories shared. I invite you to listen to the stories on the website and engage with these reflection/reaction questions (also located in the website’s About section), to generate an understanding of the stories’ larger contexts and our own connection to food and gardening:

These are only two examples of the stories shared. I invite you to listen to the stories on the website and engage with these reflection/reaction questions (also located in the website’s About section), to generate an understanding of the stories’ larger contexts and our own connection to food and gardening:

• What can these stories tell us about diverse food and gardening experiences?

• In what ways do these stories reflect or question our current food system (the way we produce, distribute consume and dispose of food)?

• Were you reminded of any specific gardening experiences or food stories while listening to the gardeners' narratives?

• Is there a place where you have a strong connection with food experiences?

• What is your story?

Why the Global Roots Oral History Project? Why Food Stories?

The stories and our reactions to them teach us about diversity, not only across cultural backgrounds but within cultures as well (Shu Rong and Mary both come from China but have distinctive cultural experiences, which are reflected in their different food experiences).

Listening to these narratives is also meant to help us identify and share our own stories, encouraging us to dig into our own experiences with food and gardening. Facilitating this project, I was able to unearth some of my own roots. I learned that my grandparents had a garden in Winnipeg. Until a few years ago, I was unaware that food could be grown in icy Winnipeg at all, let alone in my grandparents’ backyard. Learning about the garden my father grew up with made me realize that we all must have deeper connections with food than we may know. Telling our own stories and excavating histories from our past allows us to reflect on these relationships and could potentially foster new and different ways of interacting with food, plants, land and each other.

http://globalrootsstories.thestop.org/

Photo Credits: Alex Ramadan