The Fruits of Observation

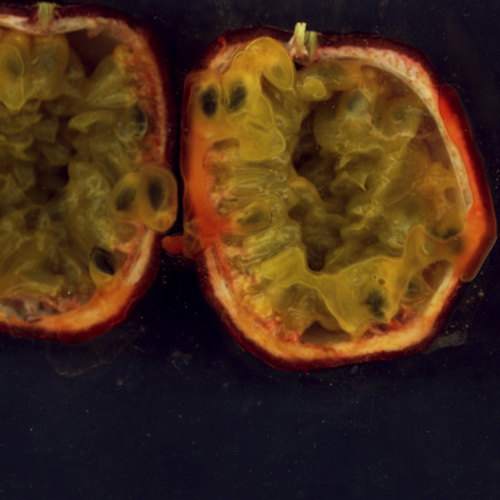

I am grateful to a rural childhood and my talented mother for initiating me to the enchantment of botanical architecture. Before having practiced the French primary school science modules simply called Observation, in which we made visual dictionaries of natural specimens, I had already acquired crystalline macro-shots of her demonstrations in the woods of Wisconsin: pulling apart the fringed, telescoping shoots she called queues de renard but which would belong to horses rather than foxes in English; sucking sweetness from the pale base of a clover petal; brushing back a verdant curtain as she whispered “regarde!†to reveal a sprig of lily of the valley, so white its faerie-sized bells rattled; and one night, for she always enjoyed fruit at bedtime, the miniature directional array of tapered ellipsoids bursting with flavorful liquid as she flayed the quinine-bitter sheath of grapefruit sections.

By engaging with the intricate structure of fruit and vegetables so often recklessly prepared and thoughtlessly consumed, we might instead infuse our existence with their exquisite sensuality. The point of the scans is to force the issue and to prolong my pleasure.

The images are part of an ongoing series called Every Garden an Eden. The first set, referencing Victorian specimen boxes with a nod to Darwin, were occasioned by Oscar Wolfman’s curatorial theme of The Creation Show (2010) for Queen Gallery in Toronto. The Merghan pieces preceded that exhibition by a year, while Devil Radish, Floating Apple, and Peau de pêche were created for the current issue of Soiled and Seeded.

Eden: Melon, 2

Eden: Pear, 16

Eden: Lime, 3

Eden: Garlic, 3

Eden: Jackfruit, 2

Floating Apple, 1-1d

Peau de Pêche, 1.1

Devil Radish, 1